Over the last couple of months, there’s been one radio ad in particular which has stood out for me. Not for its merit, or even lack of merit, but for one of the gags in it.

The ad, for mobile company giffgaff, makes a series of light-hearted predictions about what may happen in the next twelve months – one of which is that a new planet will be discovered and the name chosen for it in a public poll will be… Kevin.

The implication, of course, is that this would be a ridiculously silly name for a planet (a bit like calling an expeditionary marine vessel Boaty McBoatface). The same thing has happened in the past when a royal baby has arrived and the media have speculated on the likely name; the Guardian strongly advised William and Kate not to pick Kevin for their first child if they wanted him to be viewed positively and to have a healthy level of self-esteem.

Am I being touchy about this because I’m a Kevin? Possibly, but I’d say the feeling is one of tiredness rather than touchiness. Kevin seems to be such a lazy and over-used name for characters to be looked down on, pitied or mocked.

The neurotic, needy, weedy stay-at-home dad in Motherland? He’s a Kevin.

The carrot in the Aldi Christmas ad who ends up representing a snowman’s genitals? He’s a Kevin.

Look further back in time and it’s the same story – from Roland Rat’s squeaky-voiced gerbil sidekick, to the child forgotten by his own parents in Home Alone to the gormless-looking husband of Bev in this ad for the AA.

The example which probably springs to mind first for most people in the UK is Harry Enfield’s creation Kevin the Teenager – a lazy, surly individual who is constantly rude and ungrateful to his despairing parents. Yet even he was not the first comic Kevin to enter the national consciousness; Rik Mayall’s Kevin Turvey character predated him by a few years.

There may even have been a few risible Kevins before this; I certainly recall wondering during my own teenage years whether my mother had called me this so that I could share her own annoyance at having a widely-mocked monicker. She was a Gladys – a name which often seemed to be given to interfering, narrow-minded old busybodies on screen (Gladys Kravitz in Bewitched being just one example). Arguably my younger sister came off worse than I did, being called Karen, but that’s another story.

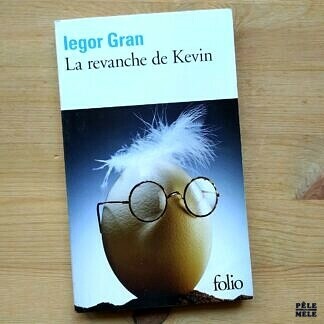

It’s not just in English-speaking countries that the name Kevin is looked down on. In France (where it was actually the most popular name given to boys between 1989 and 1994), a novel examining the situation was published in 2015. La Revanche de Kevin (‘Kevin’s Revenge’) by Iegor Gran sets out how much of a handicap the name is:

“A Kevin cannot be, does not have the right to be, an intellectual, he thinks sadly. He can be a fitness coach, a printer salesman, a supermarket manager. But an intellectual? Impossible. Being called Kevin is seen as a sign of low birth. Know your limits, Kevin!”

Meanwhile in Germany, there’s a phenomenon known as ‘Kevinismus’ – a form of discrimination against those unworthy souls who bear the name. There’s even an app called the Kevinometer which aims to help parents avoid the social stigma which comes with an unwise choice of name.

On a personal level, one of the things which generally indicates a lack of respect for those with the name is the readiness with which it is abbreviated to ‘Kev’. Even people I’ve never met before will call me Kev from the get-go, though I never refer to myself in that way. There’s an over-familiarity in the way ‘Kev’ is used, an inherent assumption that I am not to be taken seriously. Annoying as this is, though, I rarely take issue with it; it would be tiresome to keep correcting people, and it would only make fledgling acquaintanceships awkward and very likely short-lived.

There are limits, though:

New acquaintance: ‘Do people ever call you Kevvy?’

Me: ‘Only the once.’

Of course, it’s possible that there’s something about the way I carry and conduct myself that people feel able to abbreviate my name from the start. After all, I’m not aware of anyone referring to Kev Costner or Kev de Bruyne; they evidently command a level of respect which I do not.

A few more Kevins that we could look up to would be helpful in improving attitudes towards the name, but they’re few and far between. Australia had a Prime Minister called Kevin for a while, and there are currently Kevins in the US Senate and House of Representatives, plus a couple of Kévins (complete with accent) in the French Assemblée Nationale. That said, the two Kévins are both members of the far-right Rassemblement National party, so I’m not sure how deserving of respect they are.

Nor are there many up-and-coming Kevins who might be able to make a difference; according to the official statistics for 2021, only 285 babies were named Kevin in England and Wales – making it the 192nd most popular boy’s name that year.

There is, however, a financial company which seems to think that the name is sound and conveys dependability. kevin. (yes, with a lower-case ‘k’ and a full stop for some reason) is a payment services company in Europe which seems to be doing quite well; at least, they won a Fintech Company of the Year award in 2021, and as far as I can tell no one refers to them as ‘kev.’

By now, it’s possible you may be thinking: if the name is such an issue, why don’t I use a different one?

The simple fact is that it’s too late, and I’m too old, to change now. Everyone knows me as Kevin (or Kev – grrr), so it just wouldn’t be practical. And whatever her motives may have been, Kevin is the name my mother chose for me. She did also give me a middle name, but using that wouldn’t really be an option either. It’s Richard – and given the level of respect I evidently inspire, we all know what that would get abbreviated to.